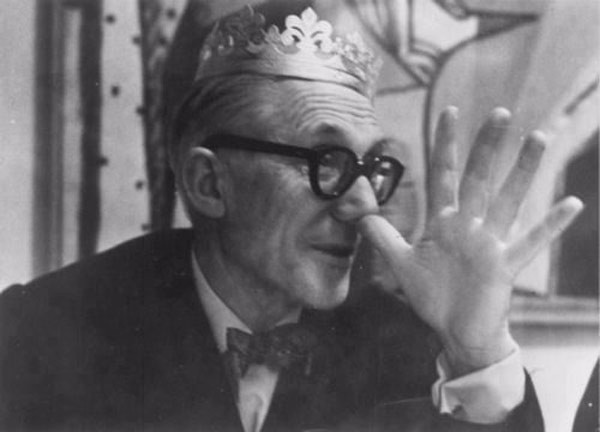

Like Le Corbusier, architects today are often remarkably loyal to their chosen eyewear style.

Architects need glasses as recognizable as a monument, from Le Corbusier, an early trendsetter, to the landscape architect Ken Smith; from Daniel Libeskind with his wife Nina, to Rafael Vinoly, double-decking; from Gordon Kipping to Michele De Lucchi with his wood glasses.

Architects need glasses as recognizable as a monument, from Le Corbusier, an early trendsetter, to the landscape architect Ken Smith; from Daniel Libeskind with his wife Nina, to Rafael Vinoly, double-decking; from Gordon Kipping to Michele De Lucchi with his wood glasses.

This time we would like to show to our readers a story written by Ruth La Ferla for the New York Times a few years ago:

This time we would like to show to our readers a story written by Ruth La Ferla for the New York Times a few years ago:

He has not had a run on them yet, but Robert Marc, a New York eyewear designer and retailer, would not be surprised to hear customers pleading, ''Make me a pair of glasses just like Daniel Libeskind wears.''

Mr. Libeskind, the Berlin architect, became the focus of attention last week when it was announced that his firm, Studio Daniel Libeskind, was one of two design teams with a project under consideration for the World Trade Center site. The other was the Think team, headed by the architects Frederic Schwartz, Rafael Viñoly and Ken Smith of New York and Shigeru Ban of Tokyo.

With their soaring towers and memorials, both concepts were the talk of the town. A few New Yorkers, however, seemed almost as impressed by the architects' eyewear. Mr. Viñoly appeared in photographs wearing two pairs of spectacles on his head -- something of a fashion signature. Mr. Smith wore his trademark dark spherical frames, and Mr. Libeskind had on a pair of heavy rectangular spectacles that highlighted his stern expression.

With their soaring towers and memorials, both concepts were the talk of the town. A few New Yorkers, however, seemed almost as impressed by the architects' eyewear. Mr. Viñoly appeared in photographs wearing two pairs of spectacles on his head -- something of a fashion signature. Mr. Smith wore his trademark dark spherical frames, and Mr. Libeskind had on a pair of heavy rectangular spectacles that highlighted his stern expression.

''Libeskind's glasses are out of control,'' said Brian Sawyer, a New York architect, his amusement mixed with admiration. He knows that for architects, signature glasses are a conscious attempt to trademark their faces, much as they trademark a building. Mr. Libeskind's frames are a particularly severe example of so-called statement glasses, meant to confer a degree of gravitas, but hinting all the while that he (or she) has raffishly artistic leanings.

Spectacles with a pronounced geometric shape are a natural style choice in a profession focused on structure and form, Mr. Sawyer pointed out. ''For me they are just like a watch,'' he said. ''I revel in all the miniature aspects of their mechanics, but they are also a beautiful thing.''

So prevalent are they as an insignia of the architect's profession that ordinary people often try to copy them.

''You never hear customers saying, 'Make me look like a lawyer,' '' Mr. Marc observed. ''It's always, 'Give me that architect type of look.' ''

At Alain Mikli or Selima Optique, among the brands professionals prefer, shoppers go in for eccentrically spherical or rhomboid shapes, some owlishly endearing, some as forbidding as Dr. Frankenstein, depending on one's point of view.

Joseph Lee, an architect with G Tects, a New York firm, favors Dolce & Gabbana glasses with a clear acrylic rim. Mr. Lee is perfectly aware that his glasses give him the aspect of a mad scientist. But their look is only fitting, he maintained. ''We think of ourselves as working in a research lab, where we like to explore different aspects of theory,'' Mr. Lee said.

It was Le Corbusier who first made owlish black spectacles a signature, thereby giving generations of followers permission to adopt a similarly geeky look. ''He made it safe to make a statement through eyewear,'' said Mayer Rus, the design editor of House & Garden magazine.

Indeed, Le Corbusier inspired Philip Johnson to design a similarly rounded pair of glasses for himself in 1934, which he had manufactured by Cartier. Ken Smith, the landscape architect, has adopted a contemporary version of Mr. Johnson's black-rimmed orbs -- the perfectly rigorous complement to his black-on-black attire.

''Just as you want to be identified with a particular design approach, you want to be known for your glasses,'' Mr. Sawyer said. ''Sometimes they are the only things that basically don't change about you.''

Often those glasses suggest a balance of weirdness and starchy conservatism. ''Of all the applied artists, the architect most often resembles a Wall Street banker,'' Mr. Rus said. ''They don't want clients to feel they are some sort of kook who is going to make them a crazy blob of a building.''

Determined to strike a sober note, a few fall back on glasses with a look that, sadly, verges on cliché. ''They rationalize their glasses as being some sort of minimalist style statement,'' Mr. Rus said, ''but they end up looking like something from an avant-garde German performance troupe.''

That kind of assessment does not faze eyewear obsessives, for whom glasses are often their only concession to style -- the ostentatiously understated equivalent of a nylon Prada coat.

Some also see them as marvels of invention. Gordon Kipping, who heads G Tects, is immoderately attached to his IC! Berlin stainless-steel sunglasses, stamped out of five sheets of metal, making their hingeless design as flexible as a hairpin.

''I just like the fact that they're an innovative technology,'' Mr. Kipping said. The architect, who spends between $250 and $350 on each pair of glasses he owns, is no less fixated on his Sandy Grendel glasses, Swiss made and designed especially for dentists.

''I like the all-titanium armature across the top, and that it comes with a visor and fiber optic light fixtures that snap on,'' he said.

Strangers quickly peg him as an architect, but that's all right, Mr. Kipping said. ''I just tell them, it's the glasses, right?''

comment