The Duomo and the Galleria are not only the centre of Milan. They are Milan. They are the symbols that identify Milan worldwide and are the best loved by its citizens.

The Duomo and the Galleria are not only the centre of Milan. They are Milan. They are the symbols that identify Milan worldwide and are the best loved by its citizens.

Built between 1865 and 1880, the elegantly majestic Galleria immediately became the city’s favourite meeting place, surrounded by the finest shops, bars and restaurants.

The Duomo was finished in 1892. The Galleria is paradoxically fifteen years older.

It was designed by an architect who believed in it with might and main, throwing his utmost physical and psychic efforts into its realisation and challenging his resilience to the pressure of such a daunting assignment. His name was Giuseppe Mengoni. He fell from the scaffolding and never saw his masterpiece completed.

The Galleria has a gigantic glass roof with a large central cupola. It is reminiscent of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, built just a few years earlier, in 1851, for the Great Exhibition in London.

Full of light and very welcoming, it must have deeply impressed the population at the time of its inauguration.

Today the Galleria is frequented by the Milanese, tourists and visitors, and is constantly teeming with people talking and eating, strolling and looking. On the corner facing the Duomo, the Galleria now also features a Market.

It is a modern Market, selling the most genuine products from a selection of greengrocery, meat, cheese and fish. All fresh and of local origin. The Market also offers a variety of eateries.

Access to the Market is by escalators, located in a small cloister.

Protruding beneath the tall arches of the porticos are the roots of a gigantic bronze olive tree.

A monument carved by Adam Lowe of Factum Arte.

The roots are there to say that we all belong to them, because they are roots that penetrate and are nourished by the same earth as ours. And because it is from these historical roots that our knowledge, strength and sense of life are derived.

The small cloister has been rebuilt today in the style of the original building, in keeping with the pattern of solids and voids on the elevation.

On the roof, the transparent awning, which had long been occluded, has been reconstructed.

Giuseppe Mengoni was a neoclassical architect whose architectural compositions combined classical stylistic elements with the technological progress typical of his time, and included the abundant use of glass and decorative cornices designed with plain geometric reliefs.

Access to the Market and its restaurants is provided along this spectacular vertical telescope, with escalators and lifts serving the various floors.

The luminous awning and the flying olive tree attract and prompt people to go up. The view extends across the earth’s crust, beyond the roots and top of the olive tree. Everything invites the eye to look upwards and into the distance.

Project

Michele De Lucchi

Project director

Alberto Bianchi

Project team

Simona Agabio

Greta Corbani

Martina Gasparoli

Federica Iula

Maddalena Molteni

Models

Francesco Faccin

Matteo Di Ciommo

Client

Autogrill S.p.A.

Location

Milano, Italia

Chronology

2013 - 2015

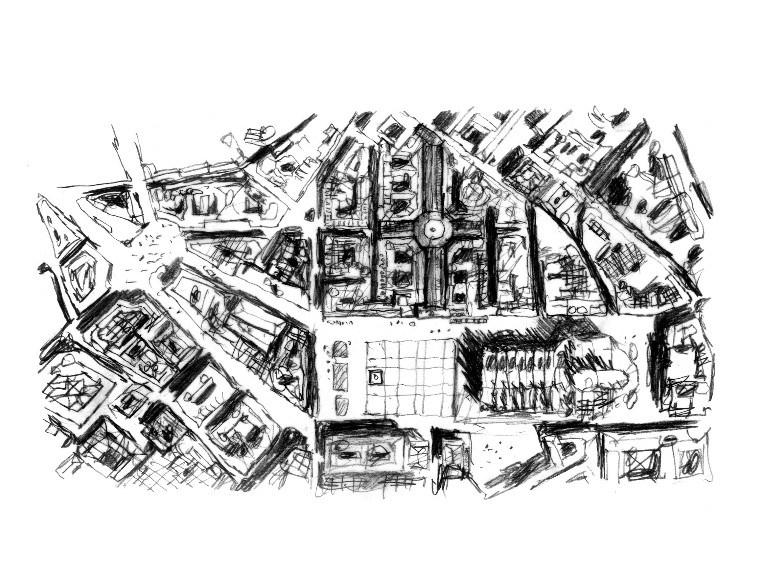

Sketches by Michele De Lucchi, 2012

Images courtesy Michele De Lucchi's Archive

comment