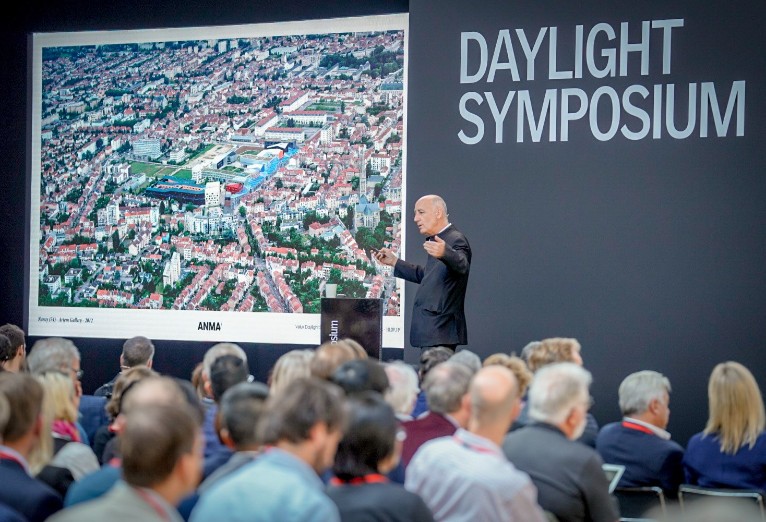

Healthy buildings have become the talk of the town in the construction industry. However, a great deal of uncertainty remains. What constitutes a healthy building, how can it best be designed and what is the role of daylight and fresh air in this process? This year’s VELUX Daylight Symposium in Paris, France, has now provided a platform for more than 600 researchers and professionals to discuss ways forward.

After decades of neglect, the merits of daylight for human well-being, health and visual delight are now being recognised in the building industry again. Architects in particular are among the pioneers in the field, guided by the example of great masters such as Louis Kahn. For Kahn, daylight was indispensable for the existence of architecture, and vice versa: “Architecture appears for the first time when the sunlight hits a wall.”

How to translate this intuitive knowledge into healthier, better daylit buildings with plenty of fresh air? And how to communicate the benefits of daylight to the building industry and the general public? These were two of the key questions discussed at the VELUX Daylight Symposium, held on October 10th at Le Carreau du Temple in central Paris, France.

©Photo Fernando Javier Urquijo / studioMilou architecture

©Photo Fernando Javier Urquijo / studioMilou architecture

The venue itself is a symbol of how the power of daylight has fallen into oblivion for a long time in our societies: Created in 1860 as a market hall, the steel and glass structure stood empty for most of the 20th century and was repeatedly earmarked for demolition. Fortunately, an outcry among the local public that demanded the preservation of the monument brought about a turnaround in political opinion. In 2007 an architects’ competition was staged in order to turn it into the event space full of daylight that it is today.

Transforming the existing building stock

Nicholas Michelin, founder of the Paris-based architectural practice ANMA was the first in the line-up of more than 40 speakers at the Symposium.

In his keynote presentation he further highlighted the role of daylight and fresh air in the transformation of historic buildings – from the design of a new roof for the Roman Amphitheatre in Nimes, France (in 1988, with Finn Geipel) to the conversion of a former Michelin factory in Clermont-Ferrand, France, into a housing complex that ANMA are currently working on.

Large, daylit spaces that bring people together are a recurring motif in ANMA’s work. At the ARTEM university campus in Nancy, France, a 700 m long, naturally ventilated gallery covered with coloured glass forms the central gathering space and circulation spine.

A similar function is performed by the 140 m long atrium – an unusual feature in any housing project in France – at ANMA’s housing project in the Bassins à Flots district of Bordeaux, France.

In a similar vein, the Paris-based architect Hugh Dutton and his practice HDA are seeking to marry poetry and engineering in the transformation of the Hotel de la Marine in the centre of the French capital. The palace-like, former headquarters of the national navy are being converted into a museum and thus made publicly accessible for the first time in two centuries. Upon completion, a roofed-over courtyard will form the central gathering space and key design feature.

“The Hotel de la Marine skylight we are working on, with the help of the VELUX Foundation, is an opportunity to celebrate daylight, encouraging it to enliven the entry courtyard of the transformed public monument”, says Dutton. Advanced daylight simulation techniques and a profound knowledge of material properties played a key role in the design, given that the narrow courtyard so far only receives a few hours of direct sunlight even in the midst of summer.

A new trend towards quantification

In the case of Hotel de la Monnaie, the roofed-over courtyard is an added benefit that the building owner initially did not even ask for. This situation is still rather typical for the building sector, where building owners are dependent on the advice of skilled designers to take the right decisions.

Ronald Schleurholts, owner of the Dutch architectural practice cepezed, says that many clients are also being guided by ill-conceived incentives: “For places and functions that explicitly require daylight, current sustainability standards often aim to minimize this.” According to Schleurholts, “the architect should then step up to, be it unrequested, use the great power of daylight. We are strongly convinced that daylight delivers better, healthier and more inspiring environments.”

Werner Osterhaus, architect and professor of Lighting Design Research at Aarhus University, highlights that there is now a tool available to assist architects in this endeavour.

“The new European Daylighting Standard 17037 places an invaluable focus on four key daylighting qualities, each one ensuring important aspects of human well-being.” In addition to the daylight levels and distribution of daylight in a given space, these include views out of windows, the extent and duration of direct sunlight exposure, and visual comfort conditions. With this broad-based scope, the new standard provides building designers with a holistic set of tools to quantify and communicate the benefits of windows and daylight in buildings in a holistic way.

Vivian Loftness, professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, USA, believes that some degree of quantification is indispensable if investors are to opt for high quality daylighting solutions.

She illustrates this with the example of a light shelf in an office façade, which reflects daylight deeper into office spaces and thus cuts down the need for electric lighting. Based on energy costs alone this element will have a payback period of over 8 years – more than what most investors will accept. Once the saved CO2 emissions and the health benefits for the workforce are factored into the equation however, the payback period drops to less than one year.

According to Loftness, the design of buildings should be all about the delight of the people that are inside them. This implies a turn away from sealed buildings with deep floor plans, which are neither beneficial for people and the planet, not resilient in the case of power failures. Instead, says Loftness, “we need systems that are turned off as long as possible – buildings that ‘surf’ through hours, days, months and seasons.”

Well daylit buildings yield higher rents

There is emerging evidence now that real estate markets are responding to this plea, and that buildings with better views and more daylight can actually achieve higher rents. According to a study presented by Christoph Reinhart, head of the Building Technology programme at the MIT in Cambridge, USA, the rents in well daylit buildings in Manhattan, New York, are on average 5% higher than in those with low daylight penetration.[1] In their analysis, Reinhart and his colleagues have included more than 5000 rent contracts in over 900 buildings in most parts of the island. The study also shows that, given the high density of Manhattan, good daylight provision is rather rare: Almost three quarters of the studied buildings have very low to low daylight levels.

Particularly in the technology sector with its often young workforce, many employers are now starting to see the benefits of healthier buildings that bring people in contact with nature. This in turn has prompted new players to enter the building sector. Yet the surrogates of nature they offer – from green walls to images of landscape projected on otherwise blank office walls – is only an inferior substitute for the soothing effect of a view out of the window or the awakening effect that a good dose of daylight has on the human body and mind. This was stressed by Lisa Heschong, co-founder of the Heschong Mahone Group and one of the pre-eminent figures of daylighting research in the United States, in her keynote presentation at the Daylight Symposium.

Intuition backed by science

There is also growing consensus among building designers that quantification should not be considered an end in itself. Many aspects of daylight design, such as views and glare, are highly dependent on subjective assessments, and may well never become 100% measurable. Nor can the relationship of daylight to place and culture, or the benefits of feeling connected to the climate outside even whilst people are indoors, ever be calculated in numbers.

This became particularly evident in the keynote presentation of Hiroshi Sambuichi, a Japanese architect and recipient of the 2018 Daylight Award of THE VELUX FOUNDATIONS and The VELUX Stiftung.

Sambuichi’s projects such as the Naoshima Hall in southern Japan, or his observatories on Mount Misen and Mount Rokko, reflect his concept of the “moving materials” sun, wind and water.

Naoshima Hall

Observatory on Mount Misen

Observatory on Mount Rokko

The mutual interaction and ever changing physical states of these natural resources – from a cooling breeze in summer to autumn mist illuminated by the rays of sunlight, or the filigree artwork of white frost forming on wire mesh – are made perceptible in Sambuichi’s architecture, and in turn define the shape of his buildings. Ultimately, the result is what Sambuichi calls “endemic architecture” – an architecture firmly rooted in its place that couldn’t possibly be built anywhere else.

Hiroshi Sambuichi’s architecture is based on his patient observation of natural phenomena and supported by tests that he performs on scale models to study aspects such as the air circulation within a building. Other projects presented at the VELUX Daylight Symposium also illustrated how experience and intuition, backed by modern science, lead to innovative results.

One example is a mixed use residential and office complex designed by Chartier Dalix Architectes and the landscape architects SLA, which will soon be built over a part of the Boulevard Périphérique, the belt motorway that encircles Paris.

The Multi-layer City, Reinventing Paris (17ᵉ)

In the project, buildings and nature form an integrated whole, with vegetated roofs and facades as well as an elevated green courtyard. The result is visually fascinating but was also backed by hard science, the distribution and selection of plants being based on the capability of the vegetation to purify the urban air. In this project, daylight and ventilation are integrated into a larger concept of biophilic design, which promises to result in a fascinating piece of urban fabric that will connect Paris to the neighbouring communities after decades of separation.

All the live photos of speakers ©VELUX Group

[1] In the study, spatial daylight autonomy (sDA 300 lux/50%) was used as a metric for daylight availability. Spaces with a sDA higher than 55% were considered well daylit.

comment