EXHIBITION _ Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light, the first solo exhibition of Labrouste’s work in the United States, highlights his work as a key milestone in the evolution of modern architecture, libraries in particular. The exhibition runs at MoMA in New York, until June 24, 2013.

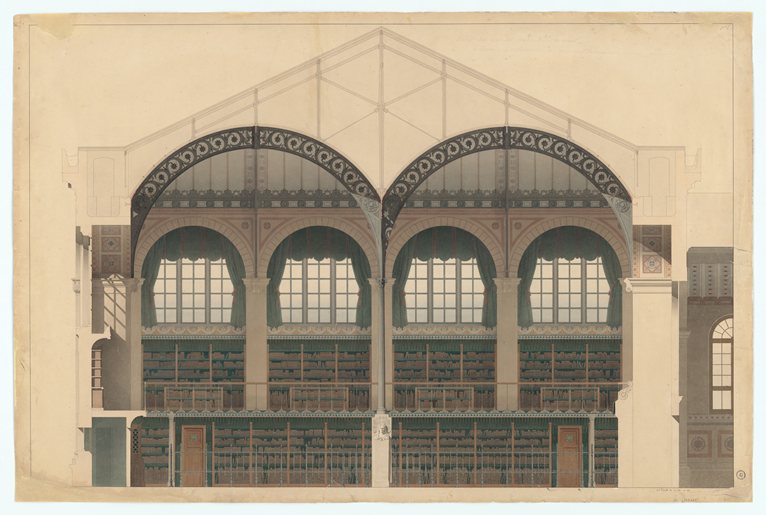

Over 200 works, from original drawings to vintage and modern photographs, films, and architectural models illustrate the power of his works, the uniqueness of their decorative details and the prominence he gave to new materials, in particular to iron and cast iron.

Henri Labrouste (French, 1801–1875) had a dramatic impact on 19th-century architecture through his explorations of new paradigms of space, materials, and luminosity in unprecedented places of great public assembly. His two magisterial glass-and-iron reading rooms in two Parisian libraries—the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (1838–50) and the Bibliothèque nationale (1859–75)—gave form to the idea of the modern library as a machine for knowledge and a space for contemplation.

Labrouste also sought a redefinition of architecture by blending art and constructive innovation with new materials and new building technologies. His spaces are overwhelming in the daring modernity of their exposed metal frameworks, exquisitely and austerely detailed masonry walls rethought for the age of iron construction, new mechanical systems and forms of heating, and stunning luminosity, using gas lighting to create spaces that are immersive and timeless. The exhibition concludes with an examination of Labrouste’s diverse and extensive influence, from his students and early followers to contemporary practitioners.

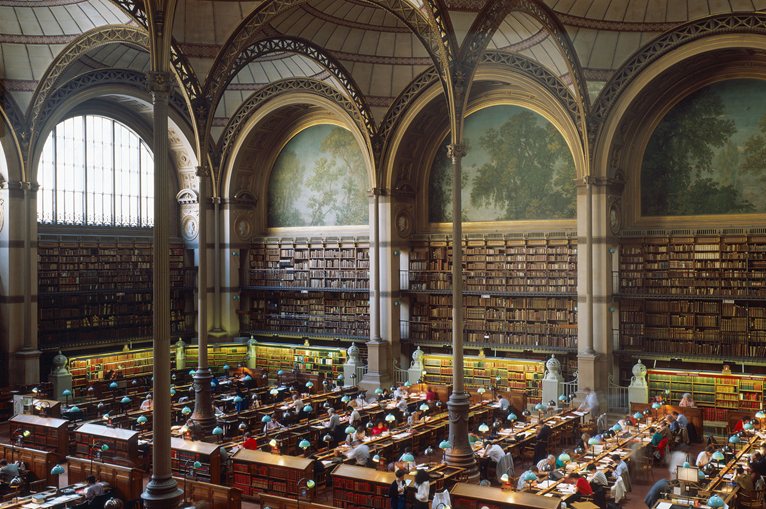

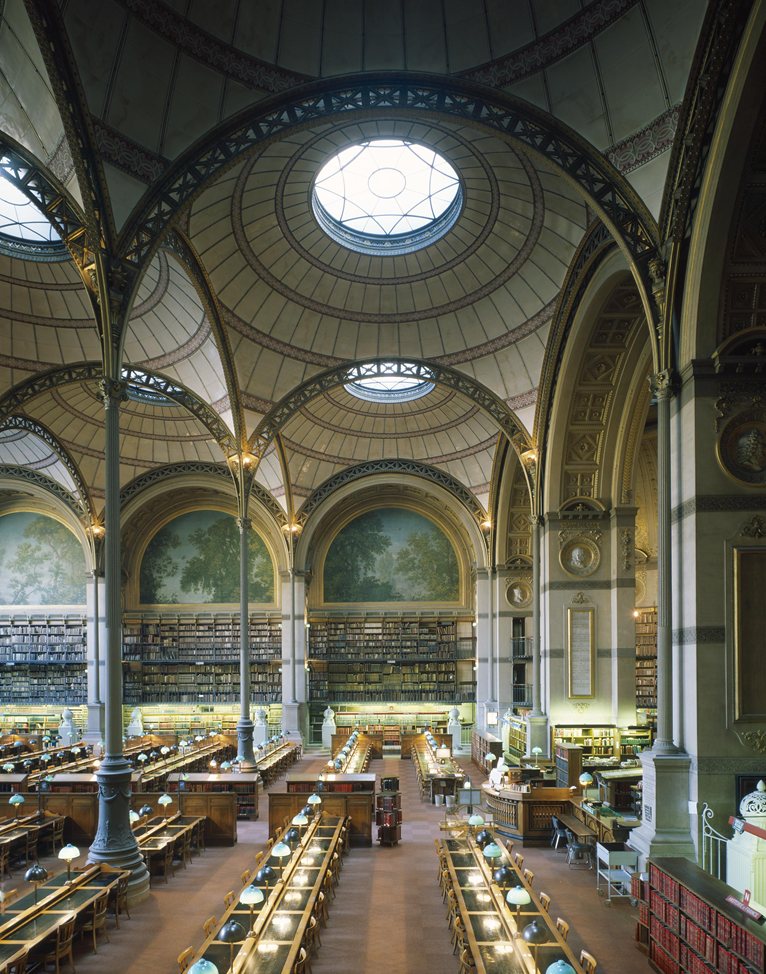

Above and top: Henri Labrouste (French, 1801-1875). Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, 1854-1875. View of the reading room. © Georges Fessy

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is divided into three sections: The Romantic Imagination; Spaces of Knowledge; and Prosperity and Affinities.

The exhibition’s first section covers the period from 1818, the start of Labrouste’s artistic training, to 1838, tracing the development of Labrouste’s philosophy of architecture and practice in two settings—ancient Rome and modernizing Paris—which Labrouste conceived of as architectural laboratories. During the five years Labrouste spent at the French Academy in Rome, he began to explore a notion of architecture as the product of layers of history, societies in evolution, and of historical change, and he proposed a new approach to architecture’s capacity to carry social meaning.

On his return to Paris, Labrouste initially focused on the ephemeral architecture of public ceremonies. With their ability to temporarily rewrite the experience of the city, Labrouste saw them as fundamental in finding an architecture of social relevance for modernity. During this time, Labrouste directed the Return of the Ashes of Napoleon I in December 1840, proposed a project for the imperial tomb in the church of Les Invalides, and won two important international competitions for the construction of an insane asylum in Lausanne and a prison in Alexandria, near Turin. Drawings of these unbuilt but influential projects are included in the exhibition.

Henri Labrouste (French, 1801‐1875). Bibliothèque Sainte‐Geneviève, Paris, 1838‐1850. Steel trusses of the reading room. Bibliothèque Sainte‐Geneviève. Photograph: Priscille Leroy. © Priscille Leroy.

The second part of the exhibition is devoted to Labrouste’s principal works as a public architect in the period of Paris’s great urban transformation in the mid-19th century, most notably two remarkable libraries: the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (1838—1850), and the restoration and extension of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (1854—1875). In each of these projects, Labrouoste deployed novel materials and techniques of both construction and information storage and retrieval. He also sought to create an immersive environment of study and reflection in the midst of the city.

The buildings were admired as much for their efficient solutions to the issues of nascent library science—including layout, flow of readers and books, and space and light, but also for their creation of veritable monuments to the role of knowledge and information in modern society. The vaulted reading rooms of the two libraries were astonishing for their lightness of structure and luminosity, and for the creation of exalted spaces for large groups of students and readers to work individually, yet in a group setting. These buildings, among the most extraordinary spatial creations in European architecture, have been touchstones for library design ever since.

Henri Labrouste (French, 1801-1875). The Pantheon, Rome. Capital and base of a column of the portico. 1825-1830. Pen, ink, graphite and watercolor on paper. Académie d’Architecture, Paris

The exhibition’s final section traces Labrouste’s extensive and varied influence on his peers and subsequent generations both through many decades of teaching but mostly through the example and wide acclaim of his two libraries.

His students worked throughout France, and key figures emigrated to the United States, the Netherlands, Turkey, and Peru. The exhibition presents the works of several of Labrouste’s students, as well as a few of the buildings constructed later on by former students of Labrouste: the Library of the Law School of the University of Paris, one of the great losses of the 1960s, designed by Louis-Ernest Lheureux (1827—1898), schools by Charles Le Coeur and the Parisian Post Office by Julien Guadet (1834—1908)—buildings that were markedly influenced by Labrouste’s teaching and practices.

Henri Labrouste, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, coupe transversale sur la salle de lecture, fin 1850, 66 x 99 cm Paris, BSG, Ms. 4273 (41) © Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris

The influence of Labrouste can also be seen in the development of metallic architecture, particularly in the mid-19th-century dream project of the Great Hall of Public Assembly. The exhibition juxtaposes Labrouste’s designs with other projects by leading architects—such as the work of E.E. Viollet-le-Duc, designs for a monumental church made entirely of prefabricated metal elements by Louis Boileau, and a project for roofing Parisian boulevards in iron and glass by Hector Horeau, and a series of built works in the last decades of the 19th century.

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York

comment