The exhibition Bruno Munari: My Futurist Past, on view at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art from 19 September to 23 December 2012, aims to investigate the activity of one of the most complex, creative and multi-faceted figures of Italian 20th century art. It will analyse Munari’s aesthetic development from his initial Futurist phase (around 1927) to the post-war period (up to 1950) when, as one of the founders of the Movimento Arte Concreta, he became a point of reference for a new generation of Italian artists. It will also illustrate how his pioneering work exerted an influence that stretched far beyond the borders of his native country.

The exhibition Bruno Munari: My Futurist Past, on view at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art from 19 September to 23 December 2012, aims to investigate the activity of one of the most complex, creative and multi-faceted figures of Italian 20th century art. It will analyse Munari’s aesthetic development from his initial Futurist phase (around 1927) to the post-war period (up to 1950) when, as one of the founders of the Movimento Arte Concreta, he became a point of reference for a new generation of Italian artists. It will also illustrate how his pioneering work exerted an influence that stretched far beyond the borders of his native country.

Curated by Miroslava Hajek in collaboration with Luca Zaffarano and the Massimo & Sonia Cirulli Archive, this exhibition will reveal the full richness of Munari’s playful, irreverent and endlessly creative career. The accompanying catalogue will include scholarly texts by Pierpaolo Antonello (University of Cambridge) and Jeffrey Schnapp (Harvard University) as well as a text by Alberto Munari (University of Padua).

Curated by Miroslava Hajek in collaboration with Luca Zaffarano and the Massimo & Sonia Cirulli Archive, this exhibition will reveal the full richness of Munari’s playful, irreverent and endlessly creative career. The accompanying catalogue will include scholarly texts by Pierpaolo Antonello (University of Cambridge) and Jeffrey Schnapp (Harvard University) as well as a text by Alberto Munari (University of Padua).

Bruno Munari

Bruno Munari

Bruno Munari was born in Milan in 1907, and lived and worked there until 1998, the year of his death. He began his career within the Futurist movement and was considered by F. T. Marinetti to be one of its most promising young exponents. From the very beginning, he was concerned with exploring the possibility of representing painting spatially through a continuous flow of forms rendered mutable through the incorporation of a temporal dimension, in accordance with the theories of Giacomo Balla and Fortunato Depero in their 1915 Manifesto ‘Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe’. Munari described the roots of his work as his ‘Futurist past’, and the movement’s ambitious scope certainly informed his kaleidoscopic career, leading him to work across a range of media and disciplines from painting to photomontage, sculpture, graphics, film and art theory. Indeed, his influences were extremely varied, also reflecting the aesthetics and sensibilities of movements such as Constructivism, Dada, and Surrealism.

In 1930 he began designing his Useless Machines – the first ‘mobiles’ in the history of Italian art – the aim of which was to liberate abstract painting from its static nature by employing the principle of causality introduced by the use of air as a force of movement for the suspended parts. The paradoxical name was intended to be a reflection on the usefulness of the useless (art) and the uselessness of the useful (machines), creating a distinction between his personal aesthetic and that of ‘orthodox’ Futurism, with its fascination with roaring machinery and its uncritical attitude towards progress.

In Paris in 1946, he created his first spatial environment entitled Concave-convex, based once again around a hanging object made of metallic mesh carefully moulded in such a way as to recall certain forms studied in topology, such as the Möbius strip. This was installed in semi-darkness and illuminated by spotlights thereby generating shadows and reflections, many of which recall the moiré patterns of certain kinetic paintings of the 1960s. Along with the spatial environments of Lucio Fontana, the Concave-convex represents one of the first installations in the history of modern European art.

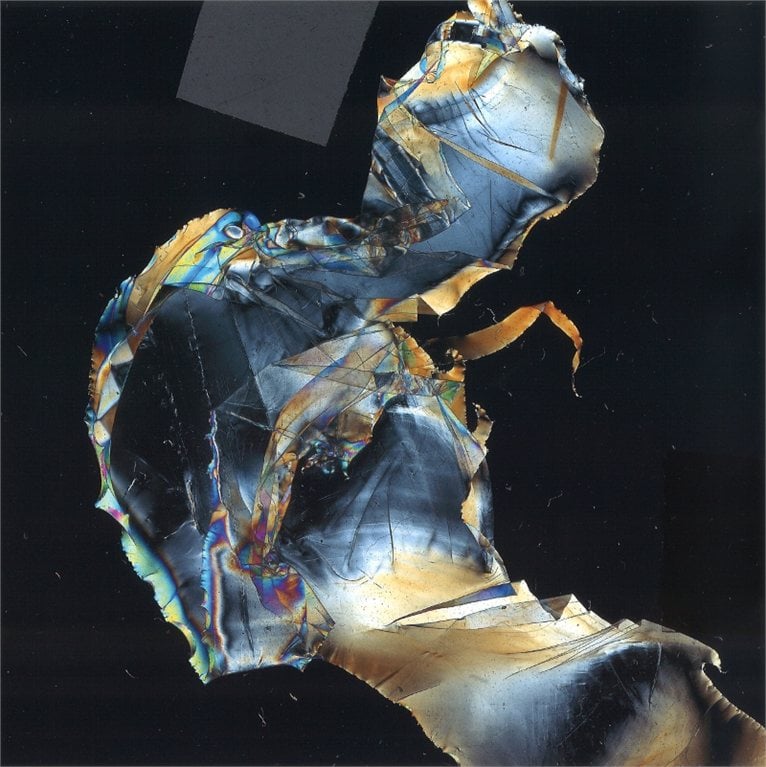

In 1951 he created the series of Arrhythmic Machines, the irregular movements of which were generated through the use of springs. In 1953 he discovered, for the first time in history, how to break the light spectrum through a Polaroid lens in a continuum given by the rotating movement of a polarising filter applied to a slide projector. The Polaroid Projects were born as logical continuations of, and theoretical complements to, the research that led to the creation of his Direct Projections.

Photo Credits:

Photo Credits:

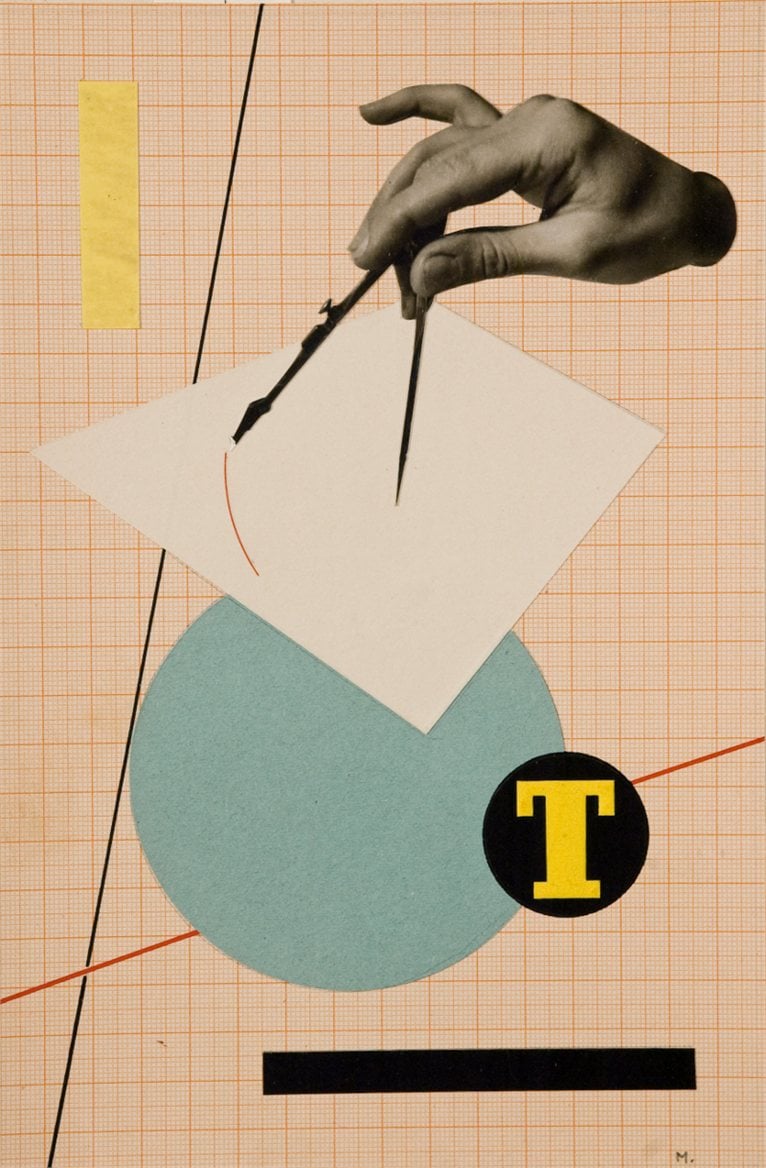

1. Bruno Munari (1907-1998) T (design for an advert for the magazine Campo Grafico), 1935 Mixed media 25 x 18 cm Courtesy Massimo & Sonia Cirulli Archive

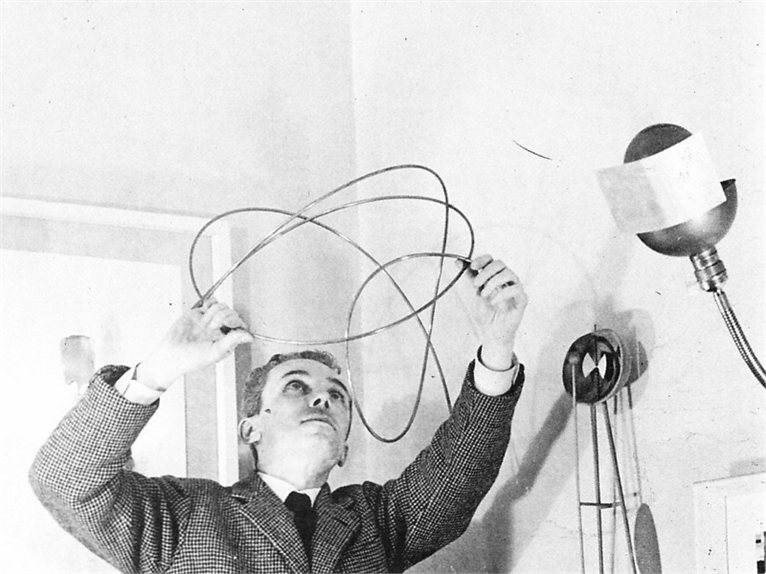

2. Bruno Munari in his studio

3. Bruno Munari (1907-1998) Curved Negative-positive, 1950 Oil on board 50 x 50 cm Courtesy Miroslava Hajek (photograph Davide Biancorosso)

4. Bruno Munari (1907-1998) Projection slide with polaroid filters, 1950 Courtesy Miroslava Hajek

comment